The Economy of Cites, by Jane Jacobs

This is a collection of my thoughts about “The Economy of Cities”. I’ll hopefully write something more polished at some point. This is the first in a reading series of books about cities and I’m looking forward to a little more compare and contrast once I’ve read a few more books.

This book is a delightful narrative analysis of how cities become and stay busy. I say narrative analysis, because this is not a scientific paper, but rather a celebration of the chaos of the city. The narrative revolves around a few pseudo-equations. I am an engineer who often shakes my head at the idiocy of pseudo-equations, so I must say that as far as pseudo-equations go, these ones more quite a lot of sense and do help in conveying Jacobs’ point clearly.

Jacobs presents cities as organic systems that thrive when they are diverse and their citizens are free to busy themselves as they see fit. The biggest contrast that she sets up is between big, chaotic cities and rigid, organized company towns. A company town is efficient and impressive, and thus able to make a lot of money when it’s product is in demand. But as needs change and the company’s product is not longer needed, the whole city declines. Whereas, a chaotic, diverse city won’t have the efficiencies required to make huge profits, it will have the agility to make new things as time goes by.

It’s this ability to make new things that Jacobs portrays as a city’s differentiating trait. What does a thriving city create? Newness. The city is a place of progress, of shaping the future. This is true of philosophies, lifestyles, products and so on. A city does not become successful by being good at any particular thing - it becomes successful by being good at doing what has never been done before.

This theme of new things makes that path that Jacobs leads us along. First she talks about the centrality and primacy of cities (vs the countryside), then she discusses how new work appears in cities, then how this new work feeds into the processes that leads to growth and many more new things.

Chapter 1 - Cities First, Rural Development later

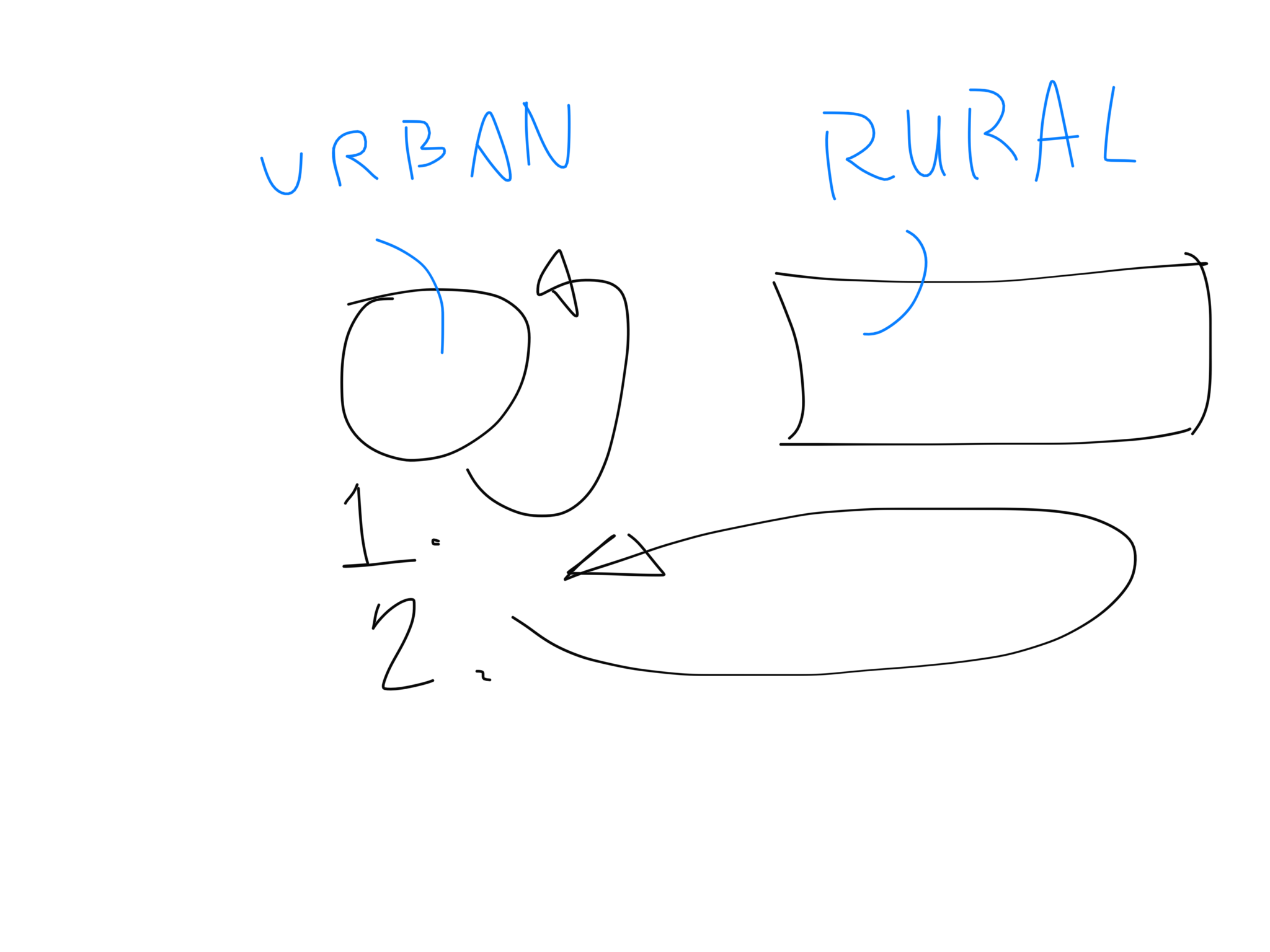

Jacobs starts by defining a flow, a direction, a broad arrow. New ideas start in a city, they are nurtured to maturity in the shelter and support of the city. Once a process is stable and prone, it moves out of the city. The demand for new things comes from cities.

Jacobs’ model has cities firmly at the centre.

Chapter 2 - How new work begins

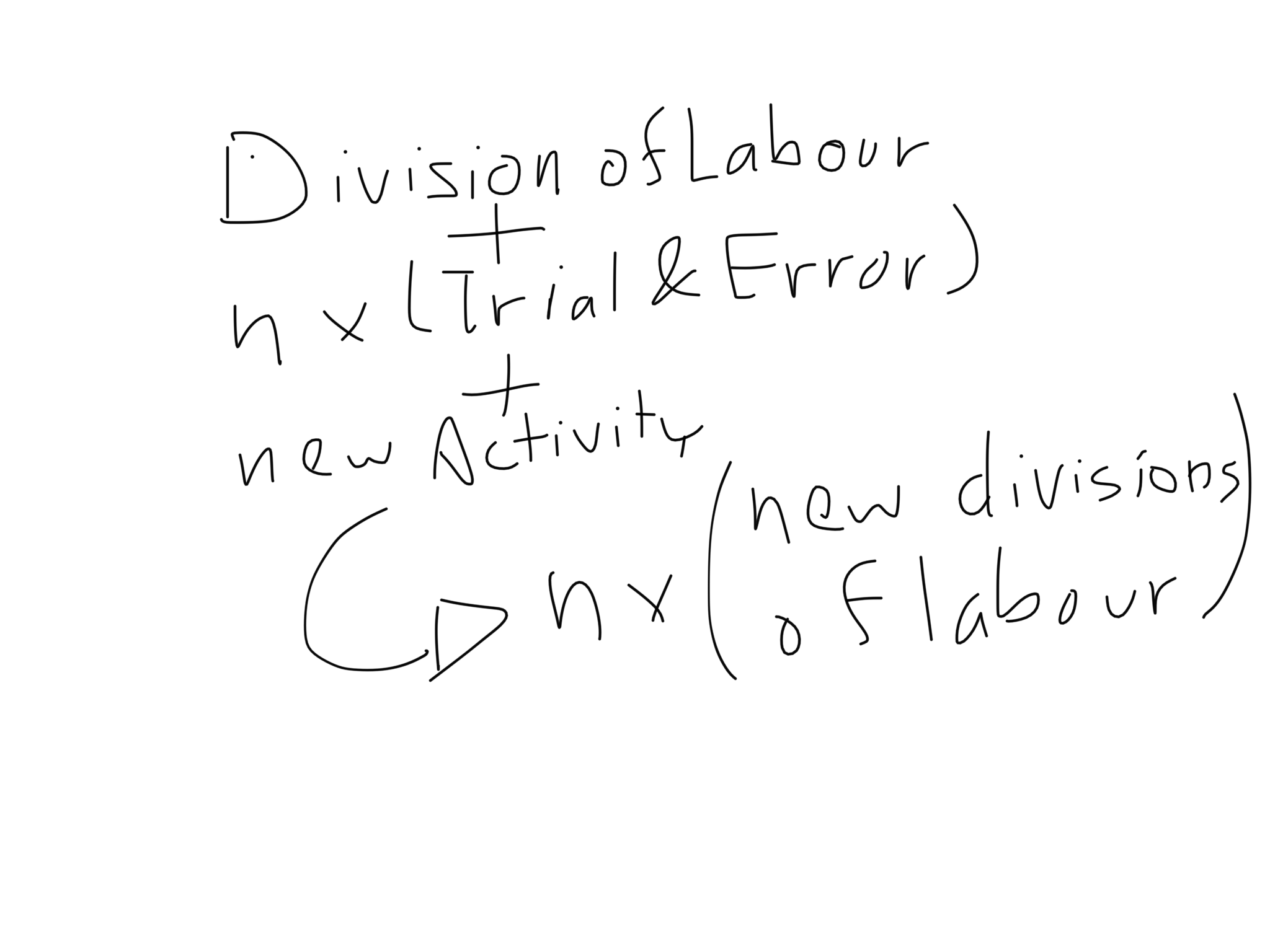

New work begins by the subdivision of a task and the transfer of ownership for each “sub-task” to those performing it. An independent sub-tasked is motivated to find new markets and new products for their skill set. An integrated supplier is motivated to stay on task and meet the existing goals and be efficient.

A degree of inefficiency is required to reproduce.

Integrated supply chains and political governance. When governance breaks down, business have to look after themselves. They need:

- physical security

- dispute resolution processes

- a financial system

When the government is not able to provide this, there will be pressure on smaller firms to join together and conglomerate. Processes in the conglomerate can handle dispute resolution and financial matters.

However, this conglomerate / integration can also bring a pressure for efficiency and focus on current work - reducing the fertility for new developments.

Chapter 4 - How Cities Start Growing

A city makes a thing, then its production moves out of the city and becomes an import. Work will always move out of the city and a thriving city is always running ahead, growing into new things. It feels so precarious, like a surfer riding a wave that collapses behind him, like a hero running across a bridge as it collapses beneath his feet.

Local suppliers become exporters in their own right and grow their base of suppliers.

Local suppliers become exporters in their own right and grow their base of suppliers.

It’s not so much a reciprocating system as a flow of business:

- Local suppliers enable exporters to thrive

- The suppliers become exporters

- These exports allow new suppliers to thrive

The reciprocating system is a static benefit between suppliers and exporters. There is a second layer of motion / progression: exporters leave the city; local suppliers become exporters; new local suppliers are created. This is business manifestation of divisions of labour creating new divisions of labour.

This progression means that the character of a city can, will and must change.

More exporters = more growth. Every new exporter plants the seeds for several other exporters (local suppliers).

An aside

Once cities grow to the point where no single entity can control them, are they then at critical mass? Does natural growth and progress require that a city not have a single dominant stakeholder? Pg. 157: “[Chicago] manufacturers were so diverse that no particular product seems to have been of special importance in itself.”

Though:

City growth is, according to Jacobs, a step by step process. One thing naturally leads to another. This is the cheapest, least risky way to proceed. So there is a paradox:

- Cities are the most expensive places to live and work. They are complicated

- Because cities are complicated and busy, the chaos and diversity of markets and suppliers allows R&D and innovation to proceed in a cheap, low-risk manner.

In a sense, the “city” - it’s established citizens and companies carries the large setup cost: systems of supply, marketing, sales, workers, etc… It allows a new business to access it just by paying rent.

Chapter 5 - Explosive City Growth

Here Jacobs introduces a second dynamic of growth. In chapter 4, we saw cities growing by exporting new things and then importing things it used to make. Here we see cities growing by supplying things is previously imported—making things it used to import.

Jacobs defines a city as a singular thing and much of her discussion of growth revolves around imports and exports ( growth is proportional to exports / imports to some power). Is this demarcation of the city boundary, and subsequent focus on what things cross it, arbitrary?

pg. 157: “In the twelfth century, Paris had been no larger than half a dozen other French commercial and industrial centres, notable perhaps only for being less specialized in any way than the others.”

pg. 157: “The city fathers [eg the primary stakeholders] tried to stop the great growth of the city … But the mighty economic force exerted by the growth of Rome’s local economy was not halted”

(Question: what sources of data exist to shed light on the question of city imports and their relationship to growth?

- tax returns for a city?

- Shipments?

- Internet traffic?

- Service contracts?

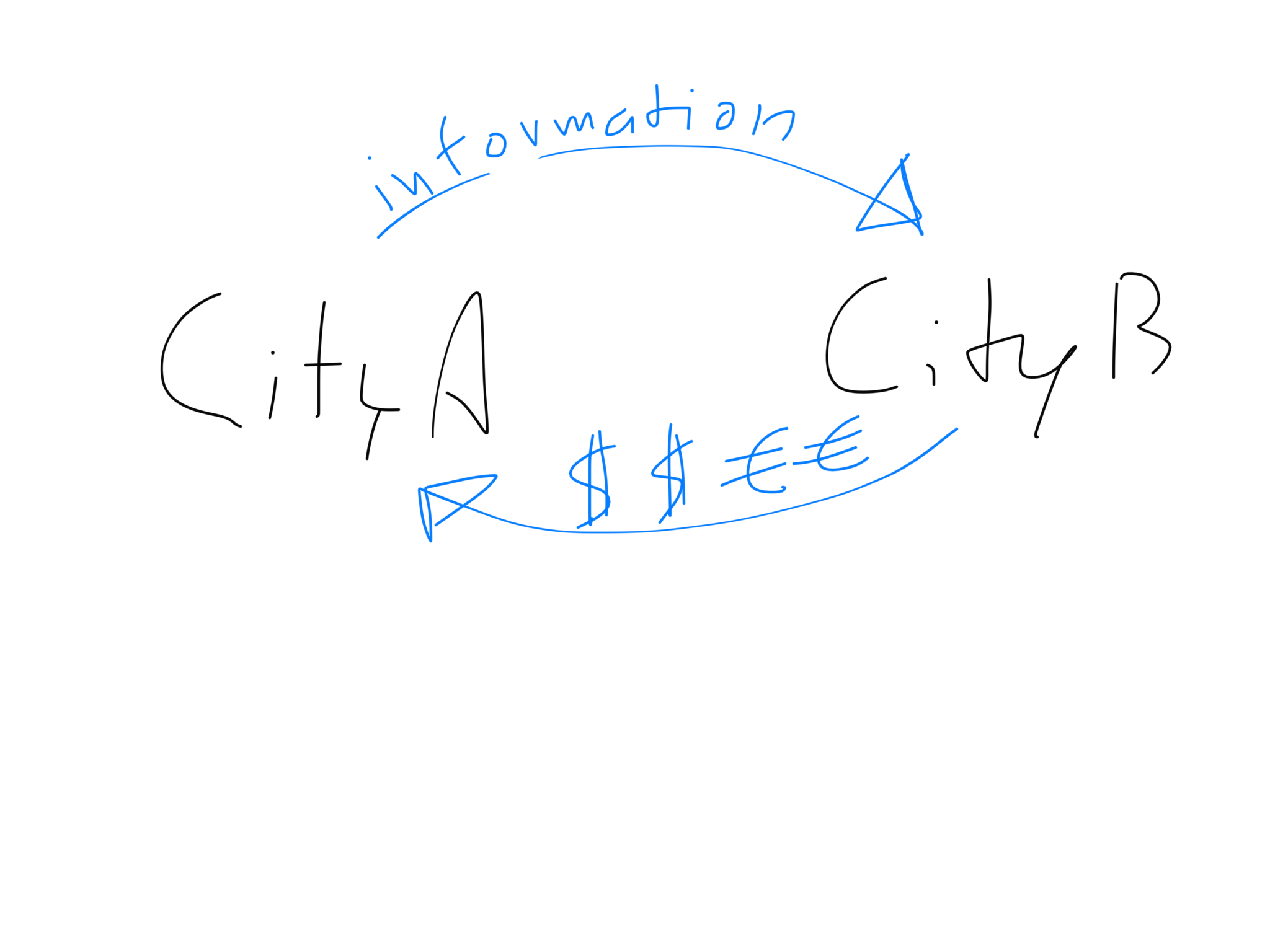

Things that can be imported and exported:

- physical goods

- Money / credit

- Advent of the Internet means Skills / services / information (work done in one city, the result of which are not physical)

Import Replacement leads to growth because to replace an import, you need to increase your headcount.

Chapter 7 - Capital for City Economic Development

Briefly, this chapter emphasizes that not only do businesses need to be set up to create new divisions of labour and new products, but financing needs to be in place for these new ventures. All the support structure for Many more types of work can be exported.